We visit the 'hidden gem' Bristol museum where some artefacts will make you cry

and live on Freeview channel 276

The George Müller Museum in Ashley Down celebrates the incredible story of how George Müller cared for and educated over 10,000 orphans in Victorian Bristol.

Müller never fund-raised or asked for money and yet, as a man of great faith and prayer, received gifts (financial and in-kind) of around £100m (in today’s value), which financed the building and resourcing of the Orphan Homes throughout the Victorian era first in Wilson Street (1836) and later at Ashley Down (1849).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMüller kept meticulous records of every child that lived in the Orphan Homes, from the first orphan in 1836 to the last orphans in the 1980s (the record system continued after Müller died in 1898).

Records of the children are kept in three places. These include the admission book, which says everything about the child before they arrived at the Orphan Home, including dates of birth, how their parents died and if they had any living relatives.

There are also ‘dismissal’ records, which record when each child left, where they went, what job or apprenticeship they went to. On occasions, they also record if a child had to leave because they were too disruptive and unruly. If a child died in the homes, a mortuary register was also kept.

The third type of record is a correspondence file which is different for each child. For some children, there’s just a birth certificate and their parents’ marriage and death certificate, and for others, it includes letters about someone requesting if a child could come to the institution and the following correspondence of questions about the child and request of documents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMüller's goal was to give children a good education to be able to send them to a good job, therefore, there was a cut-off age for children being accepted into the Orphan Homes.

They tended to accept girls until age 12 or 13 and boys until the age of 11, with some exceptions. The Orphan Homes were always full, especially during the early days, and children often slept two or three to a bed to try to care for as many people as possible.

In total, there are records of 17,556 children who lived in the Orphan Homes, some of whom are still alive.

The archive of records is kept at the George Müller Museum, and a copy is also kept at the Bristol City Archives. Members of the public can request to see the records of family members and relatives by emailing the museum at [email protected] or by filling in the form for family history on the George Müller Museum website saying who they are looking for in the records.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe staff will look them up in the database and book an appointment to see the records. If they are unable to get out of the house or don't live in Bristol, the museum can send a copy of the records as a printed copy, USB stick or digital CD to name a few.

There are a number of events coming up at George Müller Museum. On Tuesday 13th February, there will be a Victorian paper crafts free event with tea, coffee, squash and biscuits where visitors will have the opportunity to make Victorian paper crafts including Valentine's Day fans and paper dolls.

On Wednesday 14th February, visitors can learn Victorian marble games for free and there will also be tea, coffee, squash and biscuits. Later in the year, there will be an exhibition sharing some of George Müller's writings and some of the letters from the archives. So visitors will be able to come in and have a look at some of the records and kind of discover some of the stories. Dates to be confirmed.

Müllers & The George Müller Museum, 45-47 Loft House, College Road, Ashley Down, Bristol, BS7 9FG. Open Monday to Friday from 10am to 4pm.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe had the opportunity to see the records and hear the stories of some of the children who lived at the Orphan Homes. Here's what we learnt:

The first orphan, Charlotte Hill

The records date back to the earliest admission book from the Walton Street Homes and include the story of the very first child, Charlotte Hill from Gloucester Lane, who moved into the Walton Street Homes at age 11. During the 1836 Bristol Riots, Charlotte’s mother “was worried about the rioters and her money being safe and the banks being safe so [she] took out £300 from the bank and hid it so it was safe. But then [she] died and she didn't tell anyone where she hid the money. It says here, 'the mother at the time of the Bristol Riot put out 300 pounds without telling her husband where she'd put it, was suddenly taken ill’ and it says what of, 'and died without telling where the money was which seems to have caused the death of the father,'" said Ellie Manley, the curator of the museum. "So he died soon after, and so Charlotte and her sister Sarah had lots of money, £300 was a fortune in 1836, but they didn't know where it was. So [Charlotte] ends up here [at the Orphan Home] without the money, and her sister ends up here without the money. And in the file, there are some lovely letters between Charlotte and her sister. Research by one of the volunteers at the museum showed that Charlotte got married after she left the Orphan Home and moved to America with her husband where they became farmers. They had lots of children and some of her descendants are still alive today in America.

Anna-Sophia Bailey

Children came from Bristol and all over the UK, but Anna-Sophia Bailey, who was recently featured in the Red Threads exhibition, which featured the stitching and sampler work by the girls in the Orphan Homes, had not lived in this country at all. Ellie Manley, the curator of the museum, said: "Her father was in the armed forces in Australia, and they were coming back on the boat to England when she was about five years old to show her England. I don’t know if they were coming home permanently or visiting or quite what was going on, we don't have a record of that. There was a shipwreck, and a couple of days after their boat was shipwrecked, the father died, and a month after that, the mother died. And Anna-Sophia was in a foreign country, aged five, all by herself, with relatives she’d never met before, who, for whatever reason, couldn't care for her. And so she ended up being sent down here, and so her journey here started in Australia.”

Partial Orphans

By the end of the 19th-century, the Orphan Homes were emptier and the decision was made to start accepting "partial" orphans (i.e. only one of the parents had died) and the first "partial" orphan was admitted on 1 August 1901. Ellie Manley, the curator of the museum, said one of the first accounts she read when she first started working at the museum was of the father of six children, aged six months to eight years old. “He was a railway engineer and there was an accident in which he was killed unexpectedly. The mother was left alone with the children and no money coming. She couldn’t go out to work since she had six children to look after and there was no help for her. “She kept the six-month-old and the 18-month-old with her, the babies, and the other children aged three to eight, four of them, were sent down here to the orphanage. Her record made me cry because there's a letter from her in the file and she says clearly the children are here, it's the summer, the children are clearly having a good time, they haven't written a letter to mum in a long time and there's a letter from her saying tell them to write to me. I'm desperate for news’. Her tears are on the paper so she just wants to know, and that made me very emotional to think that you could be so far away from your children unable to visit them because you don't have the money and not know if they’re okay or not must have been very painful. What's nice about their records is that when each of the four children leaves the homes, every single one of their dismissal records says, 'went back to the mother who's going to find them work'. So she got them all back to her afterwards, and they came home. As soon as she could take them home, they came home. That's a really lovely end to that story. That’s one of the ones that made me cry. It's emotional. And there's just a lot of stories like that.”

Annual reports

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMüller also kept a meticulous record of all the donations that the charity had been given and published them in the annual reports which initially were published in the local newspaper. He kept note of even the smallest donations of 1p or a turnip and anonymised the names in the published annual report. Some of the annual reports also include letters from orphans who lived in the Orphan Homes thanking the homes for the support and making a donation. The Müller charity continues supporting vulnerable children around the world without requesting donations like Müller did and continues to publish annual reports. More information on the recent work made by the charity can be found here. Almost 200 years' worth of annual reports are kept in the museum.

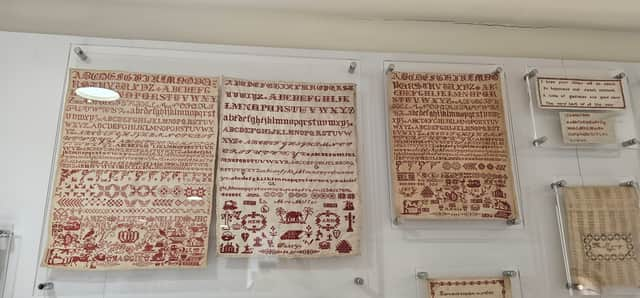

Stitched Sampler Work

The girls at the Orphan Homes learnt how to sew including samplers which are embroideries with lots of alphabet letters and different motifs. They are well known around the world and some people collect them because it's one of the best examples of Victorian school sewing that there is. Every girl signed them with their name. And you can look at the samplers and you can see what the girls were interested in and what they liked. And they're really special objects.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.